To those that may or may not know, Vipyr Security was recently invited to discuss what a malicious package reporting API might look like with the Python Software Foundation and Python Packaging oversight entities. Frankly, this is pretty cool. A step towards legitimacy, if you will. We have a lot of ideas (some of which I intend to discuss in this article). BUT I harbor concerns about the lifecycle of an ecosystem that relies entirely on third party reports to police the platform. We’ve largely held the belief that utilizing the open source community itself to secure the open source community is one of the more effective ways to tame a near endless torrent of malware. However, this comes at a cost, both in the literal sense, as the monetary burden of shifting antimalware services and detection away from the oversight body, as well as an implicit cost of organizational stability. Let’s discuss.

Crowdsourcing Open Source Security#

I got into Python anti-malware services initially as a desire to protect the users of some of the communities I was in. At the time, packages were circulating and members of the community were being deliberately targeted with malicious Python packages, and PyPI had many of the tools in place to allow for a feeble attempt at manually enumerating new and updated packages. I would wake up in the morning, make some coffee, and stare at the RSS feed for Python’s new package uploads for hours. Shockingly, this actually proved fairly effective. Many malicious packages used the same or similar names, often just updating a version number in the title or using another Python related word. (piplibraryscraper, pypilibraryscraping, etc.)

I hand rolled some tools to assist me in the spotting of these packages, but ultimately it was still very much an individual review process. I detected, reversed, and reported roughly 50 packages this way in a little under a month. But the amount of time I could spend doing this was rapidly becoming limited, and the need for automation increased.

Several individuals in the community caught wind of the project, and the engagement in the project swelled rapidly from just myself, to a team of almost 30 individuals at one point. People want to help. Malware is cool, it’s sexy, it’s interesting. Saying you handle, analyze, and prevent malicious software propagation often has the same implications as saying you regularly handle explosives. This is software designed to ruin your day, at the very least. I would say that this motivated a large portion of the interest in the project early on.

We rapidly developed a set of tools to automatically parse the Python Package Index feed using VirusTotal’s YARA rules to enumerate the behavior of these packages in a safe way. Dynamic analysis has largely been an organizational needs, but in the absence of the infrastructure to support automated dispatching of things like Cuckoo sandboxes for the analysis of the endless torrent of packages, YARA offered a comfortable starting point.

Conceptualizing the API#

Given the idea of the freedom to discuss and develop an API in conjunction with the administrative bodies at the Python Software Foundation, what might that actually look like?

Standardizing The Reporting Methodology#

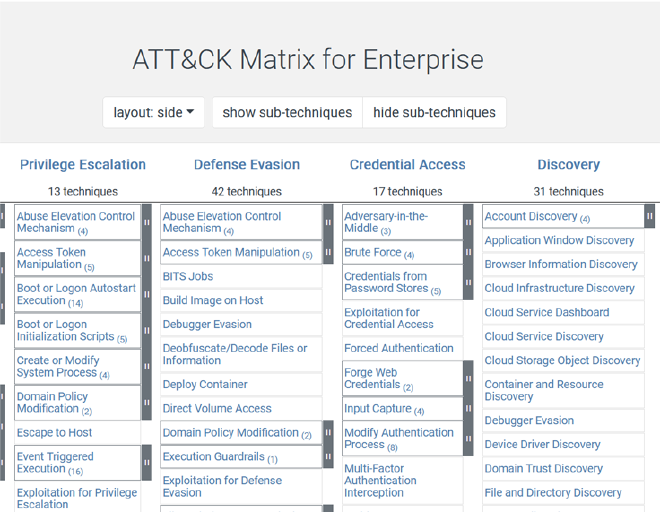

There is no shortage of standards in regards to Cybersecurity information. Commonly accepted is the ATT&CK Matrix. As it stands now, we have no introspection into what other organizations are reporting, and how they’re reporting. On our end, while it would drive an enormous amount of work to tie specific detections with YARA to the ATT&CK matrix, the most logical way we can conceptualize automated aggregation of malware tactics and techniques is the ATT&CK matrix itself. Long has the idea lingered in the back of my head that grouping YARA rules based on the ATT&CK matrix will make for a more effective reporting schema.

However, this too, has caveats. Not everything is black and white when it comes to tying the behavior of a specific detection point to a specific ATT&CK technique. This would often levy an enormous burden on cybersecurity researchers to reach the accepted, standardized format. To the best of my knowledge, each of these organizations have developed their own rules and detection techniques, even if we’re all using similar tools under the hood.

So with that in mind, could we report it by the overarching type of malware? Generic info-stealers have long since reigned supreme on the Python Package Index, and detections of things like CobaltStrike Beacons, Webshells/Reverse Shells, etc., have largely been fairly limited. That isn’t to say these attacks might not surface in the future, but at the moment, a reasonable solution for standardized reporting might simply be classifying the malware itself.

Facilitating Knowledge Sharing#

PyPI’s underlying infrastructure allows for packages to be removed from the packaging index without removing the files themselves. This is a tremendous boon to security researchers; we have the ability to retrieve samples that have long since been removed from public eyes. There are some complexities to this however. Python Packages are indexed into the PythonHosted file CDN utilizing the hash of the package itself. This means that retrieving a package requires knowledge of the hash prior to removal, as PyPI is the principle (read: only) way to obtain the hash if it was not recorded elsewhere at the time of publishing.

It is, conceptually to me at least, a reasonable ask to allow for trusted reporters to have access to an additional API on the Python Package Index that still serves information regarding removed packages. The PythonHosted link, or at bare minimum the hash of the file itself to facilitate in the reconstruction of the PythonHosted URL is a baseline requirement if packages are to be retrieved from PythonHosted in the future.

Additionally, pivoting a bit from the above, we have no introspection in the detections we are not making. I am under no illusion that our detection schemes are perfect, and I find that far more of my time is spent now looking for other organization’s detections and what we might’ve missed, than analyzing packages that we successfully detected. The ability to mark a package as removed for malicious behavior, and to communicate that message to trusted reporters is paramount if the model of crowd-sourcing PyPI security is to succeed. While this harbors implications of business intelligence degradation; that is, there is tangible money in the detections that for-profit organizations are making, relying on that layered security without communicating the results of those detections, at bare minimum the package itself, is dangerous.

The largest portion of automation in the Python anti-malware effort will come from aggregating reports from multiple organizations and using that to verdict packages. If rules are proprietary, and package removals are not communicated across the trusted reporter community, it is likely that while one organization may have an effective rule or detection, other organizations could be entirely unaware of that particular package’s existence.

The Burden of Crowdsourcing#

I spoke briefly about the literal and development costs of Python package security in the introduction. I don’t want to mince words, Vipyr Security is funded entirely out of pocket by myself, with no desire to solicit funding or incorporation. My intention is to ensure that there remains a community that is not beholden to stakeholder requirements or profit margins, that is solely focused on Cybersecurity in the open source ecosystem. Full stop.

But, while our organization is a mere drop in the bucket for the swathe of organizations detecting and reporting Python malware, what happens when it no longer becomes a profitable venture for some of the companies acting as cross-checks for each other? As third party reporting organizations may flux in the coming years as companies go under, rise, and go under again, the ability to cross check each other using the council or trusted reporter mentality may wax and wane in efficacy.

And more so, what happens when our developers lose interest? I’m unaware of other communities that are dedicated specifically to the reduction of proliferation of malware in the context of Python, and even more so– acutely aware that our numbers vastly eclipse those of some of the companies that are doing this on a for-profit scale. Our business model is unsustainable for prolonged interest of the 30 members of our community dedicating the overwhelming majority of their time towards these projects, and this overall has a negative burden on the ecosystem itself; as we’ve discussed, these reports are more effective when multiple organizations make these detections.

Closing Remarks#

This was a long one. Securing Python is hard. I’m under no illusion that we’ve created something evergreen, but it’s my hope that we can work with the Python Software Foundation to pave the way for subsequent organizations to use the tools we discuss and release to facilitate the reduction of malware in Python and open source ecosystems as a whole. I’m not sure that an organization divesting it’s entire security posture into third party reporting is something that’s been accomplished before, and I think it bears both tremendous risk if done incorrectly, and benefit if done intelligently.