Before reading this blog post, I highly recommend viewing the a blog written by my coworker titled Grab Your Chainsaw, We’re Going Hunting. Izzy originally taught me Chainsaw, and I think her blog does a fantastic job at giving an at-a-glance tutorial for how to use Chainsaw.

The scope of this blog, instead, is going to be focusing on some of the less documented functions of Chainsaw, from writing rules, to manipulating the Tau query syntax, to some real world examples of utilizing Chainsaw at-scale to threat hunt and detect evil.

Chainsaw Introduction#

While Chainsaw has functionality beyond the Windows Event Log parsing, our focus will be largely on event log parsing within the scope of this blog post.

Your First Query#

Before writing your first query, I’d recommend ensuring Chainsaw is on your PATH. Whether you’re on Windows, Linux, or MacOS, this is going to make Chainsaw much less tedious. Example commands in this blog post will refer to the ‘on-path’ Chainsaw. It is vital to understand this is not a default configuration, and will require a minor amount of additional effort that is beyond the scope of this blog post.

Chainsaw Search#

Chainsaw has two ’types’ of queries, search and hunt. We’ll discuss Search first because it’s quite straightforward until we get into the Tau syntax and query chaining. In its most simple form, a Chainsaw query might look like this:

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search JAB Windows-PowerShell.evtx

And what does this return to us?

---

Event:

EventData:

Binary: null

Data:

- Stopped

- Available

- "\tNewEngineState=Stopped\r\n\tPreviousEngineState=Available\r\n\r\n\tSequenceNumber=15\r\n\r\n\tHostName=ConsoleHost\r\n\tHostVersion=5.1.20348.2110\r\n\tHostId=ea4c6695-b4d6-44d0-aa87-a48c656684c7\r\n\tHostApplication=powershell.exe -NoP -NoL -sta -NonI -W Hidden -Exec Bypass -Enc JABQAHIAbwBnAHIAZQBzAHMAUAByAGUAZgBlAHIAZQBuAGMAZQA9ACIAUwBpAGwAZQBuAHQAbAB5AEMAbwBuAHQAaQBuAHUAZQAiADsAdwBoAG8AYQBtAGkA\r\n\tEngineVersion=5.1.20348.2110\r\n\tRunspaceId=78548a5e-76dc-40af-9cb1-cf200129bfc3\r\n\tPipelineId=\r\n\tCommandName=\r\n\tCommandType=\r\n\tScriptName=\r\n\tCommandPath=\r\n\tCommandLine="

System:

Channel: Windows PowerShell

Computer: DC-1.xyz.com

Correlation: null

EventID: 403

EventID_attributes:

Qualifiers: 0

EventRecordID: 265

Execution_attributes:

ProcessID: 0

ThreadID: 0

Keywords: '0x80000000000000'

Level: 4

Opcode: 0

Provider_attributes:

Name: PowerShell

Security: null

Task: 4

TimeCreated_attributes:

SystemTime: 2024-06-12T00:50:32.433828Z

Version: 0

Event_attributes:

xmlns: http://schemas.microsoft.com/win/2004/08/events/event

Huh, that’s kinda’ wild. (I’ll save those curious on what this might be doing, this is a whoami).

In it’s most basic form, this is the easiest way to use Chainsaw, and can be quite deadly on its own.

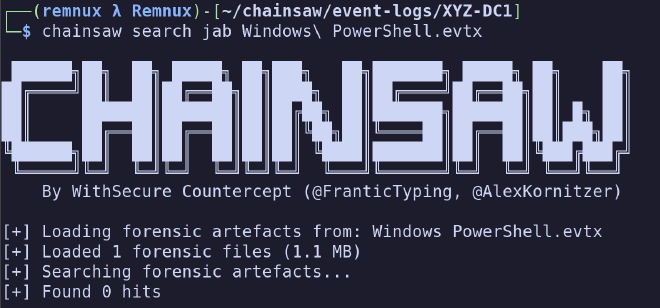

However, this is quite fragile. For instance, what if we searched for jab instead?

Huh, that’s kind of a problem, right? Often, when we’re hunting for evil, we won’t know the exact

casing of a given command. That’s where the -i switch enters the picture.

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -i JAB Windows-PowerShell.evtx

And we’re going to get the same results. That was quite a long output, so I’m not going to re-paste this every time.

We have one more ‘query parameter’ to talk about here before we start to talk about drilling down on

some more nuanced usage. This is the -e switch, which is shorthand for ‘regular expression.

Explaining regular expressions is probably out of the scope of this blog post as well, but suppose for a moment that I wanted to detect any IP addresses mentioned in event logs, and return those records for local inspection?

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -e "(25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)\.(25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)\.(25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)\.(25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)" Security.evtx

As anticipated, we’re going to get records that mention any IPv4 address within the (Security) event logs in this context.

Refining Searches - Timestamps#

When examining event logs, especially in a real world context, you’re often going to get events that do not obey your scope of interest. While it can be useful to baseline a system, often it’s a bit wasteful to start your search utilizing data that was outside the event’s timeframe.

We have a few ways to deal with this, and their usage can be a bit confusing, so let’s discuss…

The --timestamp switch is only particularly relevant in the context of the search mode for

Chainsaw, and is used to define a field with which to filter timestamps on. For clarity, there can

be multiple timestamp fields within Windows Event Logs (often in the case of webservers) and we may

want to filter based on a specific parameter.

However, this will often be used in the following context:

--timestamp Event.System.TimeCreated_attributes.SystemTime That’s a little heavy so let’s take a

moment to discuss what this actually does.

Chainsaw references key/value pairs. When we pass this into Chainsaw, we’re saying:

“Please give me the contents of the SystemTime key, which belongs to the TimeCreated_attributes

key, which belongs to the System key, which belongs to the Event key. If you’re familiar with

object oriented programming, you can think of these as properties of each other.

This will be highly useful later, but it’s fairly important to understand how to drill down on key-value pairs in Chainsaw. Take some time to look at the data if this doesn’t make sense; form opinions on what you’re seeing– run the above unfiltered search commands, and find how these fields are displayed to you.

Now that we’ve established a field to filter our timestamps on, we can discuss both the from and to

switches. --from defines a ‘start’ for timestamps, and --to defines an ’end’ for timestamps.

Windows Event Logs are in UTC, but Chainsaw exposes some ways to change this behavior. I do not

recommend utilizing this behavior, however, as forgetting to specify a timezone in later queries

can lead to incorrect conclusions.

Now, we know the switches, but what format is this anticipating? Timestamps can be specified by

the following syntax: YYYY-MM-DDTHH:mm:ss. That can be a little ambiguous, so let’s actually type

some examples:

- 2024-12-31T23:59:59

- This is a valid timestamp for “2024 December 31 at 11:59:59 PM” Note the use of 24 hour time.

- 1999-01-01T00:00:01

- This is a valid timestamp for “1999 January 1 at 12:00:01 AM” In other words, a second after midnight.

Advanced Applications of Chainsaw#

Moving on from simple string matching, Chainsaw features a robust engine based on ‘Tau’, which I’ll explain later. For now, it’s enough to understand that we’re building towards a robust query language that will let us have virtually unlimited control over which event logs we return, and we can do this both from the command line, and with Chainsaw Rules.

Refining Searches - Tau For Dummies#

Anyone looking at this might realize a problem– we have a way to string match, but we don’t really have a way to describe an event log entry directly. For instance, consider the following:

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search 4624 Security.evtx

This is problematic for a few reasons. We might be looking for Event ID 4624 here. However, what we get back isn’t necessarily just 4624 event logs. Instead, we will receive any event log which contains the string 4624. Not ideal. Let’s fix that!

Remember how we discussed the key-value relationship of event logs previously? We will now apply that knowledge to our queries. Referring to my previous query, I may actually be looking for event ID 4624, which is a successful login.

Refer to our previous Chainsaw output for some syntax clues, but maybe we want to drill down on the

Event.System.EventID parameter. Well, we can do that with Tau. Tau takes an ’expression’ and will

use that expression to evaluate documents. Anything that matches the expression will be returned.

Tau expressions can be quite interesting (and maybe lack some documentation) but they can also be very powerful in drilling down on event logs.

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -t 'Event.System.EventID: =4624'

When we specify a Tau statement, we need to quote it. This expression is evaluated using standard boolean logic, which means that the following queries are also valid:

- Event.System.EventID: >4624

- Return anything with an EventID greater than 4624.

- Event.System.EventID: !=4624

- Return anything that isn’t Event ID 4624.

Now, this one stumped me for awhile, what if we want to query a string value. Say I have a bad guy and I want to see any time they logged in via 4624. Now, I could search for their name using simple string searching, but we can be more specific than this.

Consider the following query:

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -t 'Event.EventData.TargetUserName: Administrator'

This would return any documents where Administrator is specified in the TargetUserName field. That’s problematic, but we’ll talk about that in the next section. Instead, I want to highlight one more behavior of the string engine in Tau.

Perhaps I have a series of admin accounts that I believe may be compromised. How would I search for anyone with admin in their name?

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -t 'Event.EventData.TargetUserName: *Admin*'

The above query uses * to wildcard any beginning or ending characters, and is quite fast. Again,

there are multiple ways to do this, but it’s handy for us to use wildcards here as opposed

to regular expression to have ultimate control over which fields we’re matching on.

And a final behavior to consider, what if I didn’t know the capitalization that I will be searching for?

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -t 'Event.EventData.TargetUserName: i*admin*'

The i prefix in this string engine will cause this search to be case insensitive.

It’s important to understand these concepts, because they will be applied later in the rules section where we’ll write YAML-based rules that mimic this Tau syntax.

Chaining Queries#

Now that we’ve spelled out how to utilize Tau parameters, we can actually start to construct more advanced queries. Suppose I wanted to detect users who logged in with accounts such as ‘admin’ and ‘administrator’, using a network login.

To drill down on this, let’s define the problem:

- We’re looking for successful login events (Event ID 4624)

- We want a specific user name parameter.

- And we want to see logins of type 3.

We can define this with three different Tau queries:

-t 'Event.System.EventID: =4624'

-t 'Event.EventData.LogonType: =3'

-t 'Event.EventData.TargetUserName: i*admin*'

If any of these are unintuitive to you, do the following: Take the first query, run it. Now, identify where I obtained the LogonType parameter and TargetUserName parameters from, and then craft those queries independently.

This is ‘drilling down’ on logs, and is a common analyst process. You identify a broad behavior, then begin to specify queries to limit your output to certain behaviors.

So if we wanted to combine these queries, how would we go about it? Well, by default, you can specify

multiple parameters with no issues and they are ANDed by default. So if we wanted to solve our problem,

we might do the following…

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -t 'Event.System.EventID: =4624' -t 'Event.EventData.TargetUserName: i*admin*' -t 'Event.EventData.LogonType: =3'

This functionality is incredibly potent at rapidly cutting through event logs, and can allow you to essentially build out a custom query to pull out virtually any sort of evil from the event logs simply by searching. We can apply this to IP addresses…

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -t 'Event.System.EventID: =4624' -t 'Event.EventData.IpAddress: 192.168.65.131'

Note that I said Chainsaw, by default, will AND these parameters. What if we wanted to specify

an OR? While this is quite limited in usefulness, we might consider passing the --match-any switch,

which will instead change the default behavior of all of these queries to OR. So in the case

of the above query, we will match any records that have an EventID of 4624 OR any records that have

an IP address of 192.168.65.131. Handy, but queries must be crafted carefully since you cannot control

which expressions are ANDed and which expressions are OR’d.

Putting It All Together#

Now we have all the components necessary to construct advanced Chainsaw queries directly from the command line. Perhaps we believe a threat actor utilizing usernames similar to ‘hacker’ is logging in via network login from IP address 192.168.65.131. We know that the incident took place on April 1 2024 between the hours of 8PM and 10PM UTC. Take a moment to consider how to craft this query before looking at the answer…

┌──(remnux λ Remnux)-[~/chainsaw/event-logs/XYZ-DC1]

└─$ chainsaw search -t 'Event.System.EventID: =4624' \

-t 'Event.EventData.TargetUserName: i*hacker*' \

-t 'Event.EventData.LogonType: =3' \

--timestamp Event.System.TimeCreated_attributes.SystemTime \

--from 2024-04-01T20:00:00 \

--to 2024-04-01T22:00:00

While that’s quite long, we can now detect any network logins that took place during that time from a user that may have matched that username. We can start to add/subtract information as necessary to refine our query. Consider that we may be dealing with multiple event logs from multiple systems? Can you think of how this might help us recognize lateral movement across multiple systems?

Hopefully the usefulness of that information is becoming readily apparent.

Conclusion#

This is first part of a three-part series, to keep this from becoming… too painfully long. However, I would recommend spending some time getting familiar with the more advanced query behaviors I’ve discussed here, as they’ll be highly applicable to writing chainsaw rules in the future during the Chainsaw Hunt mode, where we can specify either SIGMA rules (and mappings) or rule files, which are essentially just YAML Tau queries, with the added benefit of having ultimate control over the boolean logic of matches, and the ability to aggregate results based on various fields returned.